Image-Pretrained Vision Transformers for Real-Time Traffic Anomaly Detection

Motivation

Traffic anomaly detection (TAD) is critical for autonomous driving, requiring both high accuracy and low latency. The task involves identifying abnormal or dangerous events from ego-centric dashcam footage in real-time — a binary classification problem at the frame level.

Recent work such as Simple-TAD shows that a simple encoder-only VideoMAE model with strong pre-training can outperform complex multi-stage architectures, achieving 85.2% AUC-ROC on the DoTA benchmark. However, video-pretrained models like VideoMAE process 3D spatiotemporal tokens, making them computationally expensive for edge deployment.

This raises a natural question: can we trade some accuracy for significantly faster inference by using lighter, image-pretrained backbones instead?

Approach: VidEoMT-TAD

We adapted VidEoMT, a video instance segmentation model, for the TAD task. The key idea is to use a frame-based image foundation model (DINOv2) instead of a video foundation model, and handle temporal modeling through lightweight query propagation.

The architecture works in three stages:

Frame-independent encoding: Each frame is processed independently through a DINOv2 ViT-S/14 backbone, producing 16x16 = 256 patch tokens per frame.

Query-based cross-attention: Learnable query tokens attend to patch features via cross-attention in transformer blocks 9-11. This is where the model learns what to look for in each frame.

Temporal aggregation: Queries are propagated across frames using a GRU-based updater, enabling the model to track evolving patterns across time. The final frame’s query representation is used for binary classification.

For multi-query configurations (Q > 1), we aggregate per-frame queries via max pooling, which preserves the strongest response per feature — effective because anomalous events tend to strongly activate specific queries.

Key Findings

Self-supervised pretraining matters most

We compared different backbone initializations under controlled settings:

| Pretraining | AUC-ROC | FPS |

|---|---|---|

| DINOv2 (self-supervised) | 76.5 | 190 |

| ImageNet-1K (supervised) | 72.6 | 202 |

| ImageNet-21K (supervised) | 72.0 | 197 |

DINOv2 outperforms supervised ImageNet by +3.9 pp AUC-ROC, suggesting that self-supervised representation quality matters more than label diversity for anomaly detection. Interestingly, more categories (ImageNet-21K) doesn’t help.

GRU-based temporal modeling

A GRU query propagator maintains hidden state across frames, enabling the model to track evolving temporal patterns. Compared to a simple linear projection baseline:

| Propagator | AUC-ROC | FPS |

|---|---|---|

| GRU | 78.1 | 200 |

| Linear | 76.3 | 189 |

The GRU improves AUC-ROC by +1.8 pp while maintaining comparable throughput, validating that explicit temporal memory benefits anomaly detection.

The accuracy-efficiency trade-off

Our best model achieves 78.1% AUC-ROC at 200 FPS — 2.6x faster than Simple-TAD (85.2% at 76 FPS), trailing by 7.1 pp. All models far exceed the 30 FPS video rate, leaving significant headroom for real-time deployment.

| Model | AUC-ROC | FPS |

|---|---|---|

| Simple-TAD (VideoMAE-S) | 85.2 | 76 |

| VidEoMT-TAD ViT-S (Q=50, GRU) | 78.1 | 200 |

| VidEoMT-TAD ViT-S (Q=1, GRU) | 77.3 | 200 |

| VidEoMT-TAD ViT-S (Q=1, Linear) | 74.9 | 190 |

When to use image-pretrained models for TAD

Our findings suggest image-pretrained models are appropriate when:

- Latency-critical: Applications requiring >100 FPS (e.g., parallel multi-camera processing)

- Resource-constrained: Edge devices where VideoMAE’s memory footprint is prohibitive

- Acceptable accuracy: Scenarios where ~78% detection rate meets requirements (e.g., driver alert systems with human oversight)

Conversely, safety-critical applications requiring high recall should prefer video-pretrained models despite computational costs.

Conclusion

This internship investigated the trade-offs of using image-pretrained ViTs for traffic anomaly detection. The key takeaways:

- DINOv2 > ImageNet: Self-supervised pretraining outperforms supervised ImageNet by 3.9 pp AUC-ROC

- Temporal modeling helps: GRU-based query propagation improves AUC-ROC by up to 1.8 pp over a linear baseline

- A significant accuracy gap exists: 7.1-10.3 pp compared to video-pretrained VideoMAE, offset by 2.5-2.6x faster inference

These results provide practical guidance on when image-pretrained backbones are suitable for TAD deployment.

Per-Category Analysis

Breaking down the accuracy gap by anomaly category reveals where image-pretrained models fall short and why:

| Category | Gap (pp) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Start/Stop | −4.5 | Static anomaly — spatial cues alone suffice |

| Obstacle | −7.3 | Stationary obstruction detected from single frame |

| Lateral | −7.7 | Side-to-side motion captured by spatial features |

| Oncoming | −8.9 | Focuses on the approaching hazard |

| Turning | −9.0 | Most common type — attends to turning vehicle |

| Leave Left | −10.1 | Vehicle departing lane leftward |

| Moving Ahead | −10.5 | Forward collision detected through spatial proximity |

| Leave Right | −11.2 | Vehicle departing lane rightward |

| Unknown | −12.8 | Ambiguous scenarios requiring temporal context |

| Pedestrian | −16.4 | Hardest category — trajectory understanding needed |

The pattern is clear: categories where the anomaly is spatially evident (e.g., a stationary obstacle, a stopped vehicle) have small gaps (−4.5 to −8.9pp). Categories requiring temporal reasoning (e.g., predicting a pedestrian’s trajectory, understanding lane-departure dynamics) show large gaps (−12.8 to −16.4pp).

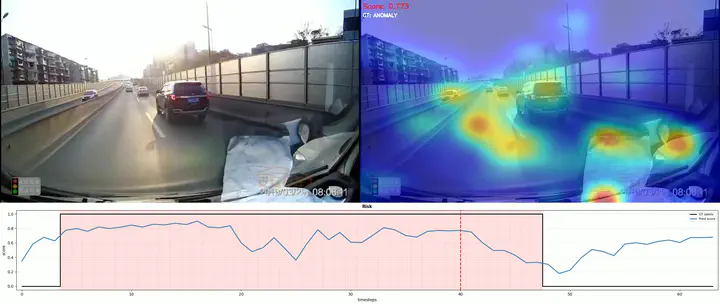

Attention Visualization

The model learns to attend to anomalous regions. Heatmaps show attention weights aggregated across queries, with confidence scores indicating anomaly probability.

Below are visualizations grouped by gap severity. Even for the hardest categories, the model attends to the correct regions — the failure is in temporal dynamics, not spatial attention.

Small gap (−4.5 to −8.9pp)

Medium gap (−9.0 to −11.2pp)

Large gap (−12.8 to −16.4pp)

Resources

Acknowledgment

This work was conducted at the Mobile Perception System lab, Eindhoven.